Social engineering is evolving rapidly. What began as suspicious emails and phone‑based scams has escalated into hyper‑personalized, AI‑driven deception. Organizations face threats like deepfakes of their CEO's voices and fake Zoom invites sent to finance employees.

Attackers don't just target systems; they target people. Focusing solely on firewalls, antivirus, or technical cybersecurity isn't enough. At Adaptive Security, we believe this shift calls for a behavior-first defense—one that empowers employees, reinforces trust controls, and builds real human-centered resilience.

In this article, we define what social engineering attacks are, trace how they've evolved, and explore real‑world examples and defenses grounded in both human psychology and modern security practices.

What are social engineering attacks?

Social engineering attacks manipulate human psychology to trick people into revealing sensitive information, approving transactions, or installing malware. Instead of exploiting software flaws, attackers exploit trust, fear, authority, and urgency.

Social engineering isn't new. The first phishing emails appeared around 1995, and as email and web use exploded, phishing became the dominant vector for social engineering. Today, hackers harness AI and deepfake technologies to create convincing fake voices or video calls, forge documents, or automate personalized scams.

What started as simple spam has evolved into targeted, enterprise-level threats. Modern cybersecurity can't rely on technical controls alone—protecting human behavior is now essential because attackers target people, not just systems.

Common types of social engineering attacks

Social engineering doesn't rely on a single method. Attackers draw on a toolbox of psychological manipulation techniques, email, phone, SMS, physical deception, and more, to trick people into bypassing defenses. Here are some of the most prevalent examples of social engineering seen today.

Phishing scams

These are the classic fraudulent emails or messages that impersonate trusted senders (banks, vendors, internal leadership, etc.), tricking the recipient to click a link, open an attachment, or enter credentials.

For example, a company employee receives an email appearing to come from HR or IT asking them to "reset their password immediately" via a link. That link leads to a fake login page that captures their credentials.

Phishing scams exploit familiarity and a sense of urgency. Spear phishing makes the recipient think the request is legitimate and time-sensitive, which reduces skepticism and increases the chance of a click or credential entry.

Vishing (Voice phishing)

Instead of email, attackers use phone calls, often spoofed to look like they come from a trusted number, to trick people into revealing sensitive information, login credentials, or performing actions. Attackers gain access to a wide variety of confidential information, from credit card numbers to bank account information.

A typical example could involve a caller who claims to be from the company's bank or internal IT support, warns of suspicious activity or a "security issue," and pressures the employee to confirm account details or reset credentials.

Vishing world because phone-based communication feels personal and authoritative, especially if the caller spoofs a legitimate number or uses convincing details. Fear or urgency ("Your account is compromised…") often makes people comply.

Smishing (SMS phishing)

Similar to phishing, but using SMS/text messages instead of email. Attackers send fraudulent texts appearing to come from reputable organizations, urging recipients to click malicious links, call a spoofed number, or reply with confidential data.

An example of a smishing attack could be a text message claiming to be from a bank: "Your account has suspicious activity—verify now," including a link that leads to malicious software or triggers malware download.

Smishing is effective since people check texts quickly, often trust SMS more than email, and may take action impulsively, especially when messages are brief and urgent. Recent data shows smishing incidents have surged as attackers pivot away from email-focused attacks.

Pretexting and impersonation

In pretexting, attackers invent a plausible scenario (the "pretext") that gives them reason to ask for private information or access. Often this involves impersonating someone the victim trusts (a colleague, vendor, IT staffer, authority figure). It's also called business email compromise (BEC) and is a serious cyber threat.

For example, an attacker calls an employee pretending to be from internal IT, claiming there's a system problem and they need the employee's credentials to fix it, or sends a message impersonating a vendor, asking for payment or confidential company data.

Pretexting takes advantage of the fact that people generally want to be helpful, especially if the request seems legitimate and comes from an authoritative or familiar source. The pretext offers a believable reason to override suspicion.

Baiting and physical social engineering

Rather than using digital channels, baiting involves physical or real‑world temptations to trick individuals. For example, leaving a malicious USB drive in a public place, hoping someone will plug it into a company computer, or offering "free" software/download that contains malware.

Other physical tactics may include tailgating (unauthorized people following employees into restricted areas) or in-person impersonation (pretending to be a delivery person, technician, etc.) to gain physical access.

An attack could involve a USB drive labeled "Confidential – Q4 Bonuses" left in the office kitchen. An employee curious about the label plugs it into their workstation, instantly compromising the network with malicious websites or malicious code.

Curiosity, convenience, or goodwill often override caution in a baiting or physical attack. Employees may rationalize "it's probably fine" when faced with a seemingly innocuous item or a person who "should" have access.

The rise of AI-powered social engineering

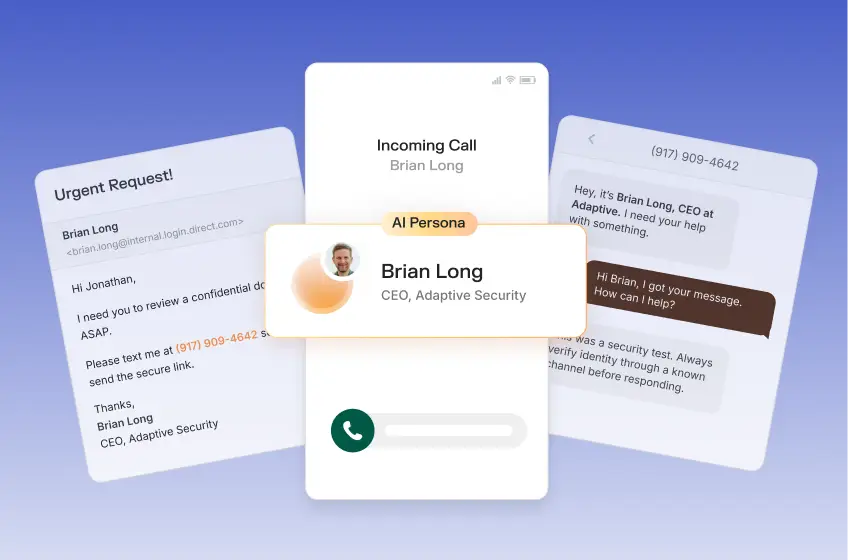

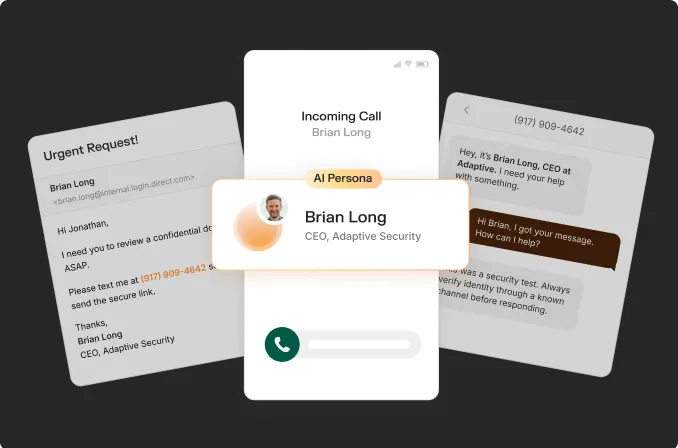

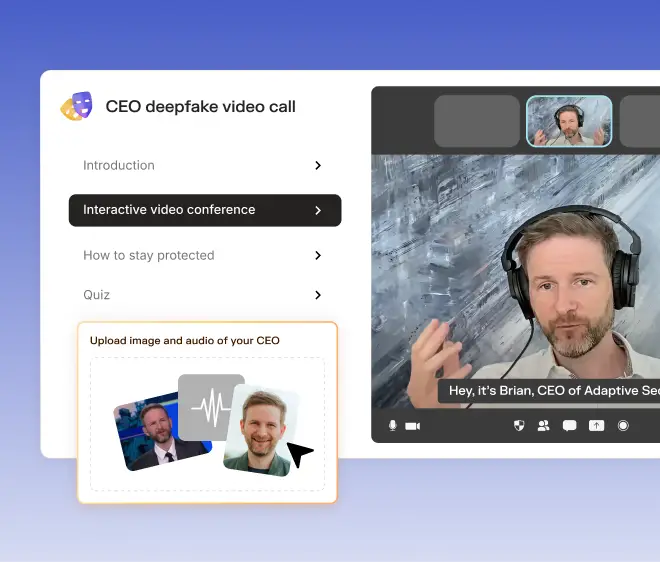

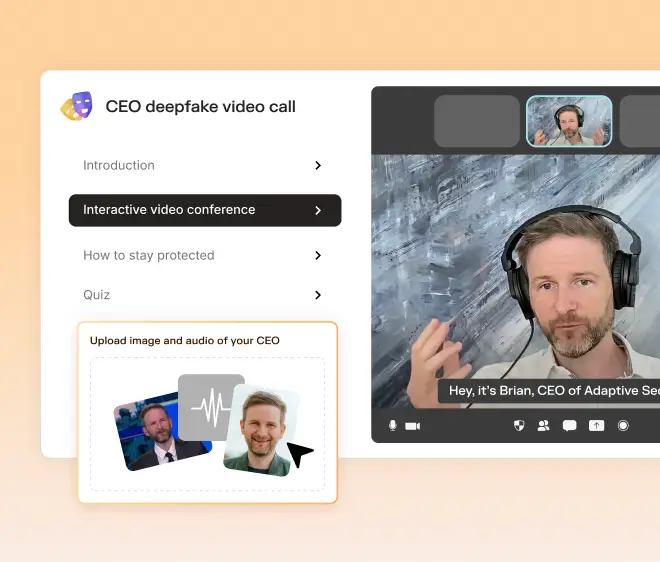

Attackers increasingly leverage AI tools such as chatbots, voice cloning, and video deepfakes to impersonate trusted individuals and organizations, dramatically raising the stakes for security.

In a 2024 incident involving the global engineering firm Arup, criminals used an AI‑generated deepfake video call to trick an employee into approving a transfer of approximately $25 million. In another case, the global advertising group WPP was targeted by a deepfake voice‑cloning scam of its CEO. These are stark reminders that no company is immune.

AI enables attackers to:

- Generate contextual, personalized lures at scale: drafting convincing email or message content tailored to the target's role, company, or personal background.

- Clone familiar voices or faces: savvy employees may be fooled when they "see" or "hear" a trusted executive.

- Automate multi‑step attacks: attackers can maintain multi‑round conversations that adapt to a person's responses, increasing plausibility and lowering suspicion.

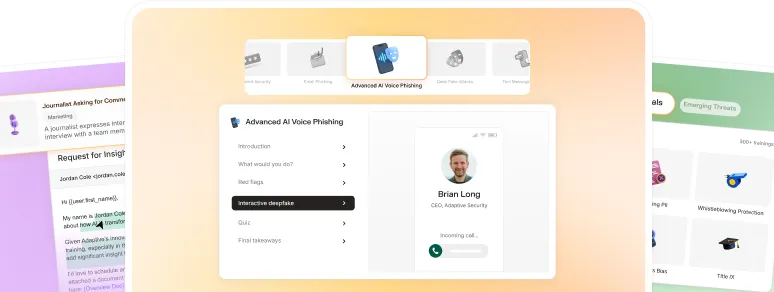

At Adaptive Security, we anticipate and simulate these emerging threats in our training, using mock phishing, voice‑spoofing, and even deepfake‑scenario drills across channels. We help organizations build resilience to phishing attacks and AI‑driven, human‑targeting scams that bypass traditional controls.

Why employees still fall for social engineering

While technical defenses (MFA, filters, spam detection) are vital, they can't neutralize deception that happens through human channels. Data supports this: a 2024 survey estimated that about 68% of breaches stemmed from human factors, including social‑engineering crimes or honest mistakes.

Social engineering works through urgency, authority, fear, or empathy. These triggers provoke quick, emotional reactions, often before rational thinking kicks in. A study on phishing found that urgency and scarcity appeals significantly increased success rates.

Adaptive Security treats human risk as a dynamic, measurable attack surface. That means regular testing, continuous training, and behavior‑driven simulations, not just annual awareness sessions. Only by acknowledging that people are the common denominator in nearly every breach can organizations build a resilient security culture.

Real-world scenarios: How social engineering attacks unfold

To understand the true danger of social engineering, it helps to walk through cybercrime examples. These stories show how easily trust can be manipulated and why proactive, human-focused defenses like Adaptive Security's AI-driven simulations are critical.

A finance team hit with a CEO deepfake request

On a quiet Friday afternoon, a mid-sized technology company's finance manager receives a Slack message that appears to come from the CEO. It's brief and urgent: "Need you to wire $175,000 to a Hong Kong supplier ASAP. Running into issues with procurement. Can you handle?"

Moments later, a video call request follows. On-screen is the CEO, or so it seems. The voice, the face, and the mannerisms all match. The "CEO" explains the situation quickly, citing a confidential acquisition in progress and legal constraints that prevent full disclosure.

Pressured by authority, urgency, and what appears to be a legitimate visual confirmation, the finance manager authorizes the wire transfer. Hours later, she learns the CEO never made the request. The attacker used a deepfake video and voice clone generated using publicly available media and AI tools.

These AI-powered impersonation attacks are growing in frequency and sophistication. At Adaptive Security, we help organizations simulate deepfake‑style executive impersonation scenarios, training employees to verify requests through known channels, no matter how convincing the source appears.

An HR rep tricked into opening a resume laced with malware

A hiring manager in HR is reviewing applications for an open engineering position. One candidate emails a polished cover letter and resume attachment. Although everything looks normal, the file is a cleverly crafted PDF containing embedded malware designed to exploit a known vulnerability in the company's document reader software.

The malware silently installs a backdoor that gives attackers remote access to the company's network. Within days, sensitive employee records are exfiltrated, triggering a costly breach notification process and regulatory fines.

This attack didn't target the IT infrastructure. It targeted human behavior: curiosity, routine processes, and a desire to respond promptly.

Together, these examples show how modern social engineering attacks exploit everyday workflows, authority, and trust—not technical gaps. As AI-driven impersonation and malware delivery continue to evolve, organizations must move beyond awareness alone and actively test how employees respond under real pressure.

Adaptive Security's behavior-based simulations and reporting help teams identify risk early, reinforce verification habits, and measurably reduce human-driven attack exposure.

Adaptive Security helps you stay ahead of attackers

Today's threat actors leverage artificial intelligence, emotional manipulation, and channel-spanning tactics to breach even the most technically secure environments by targeting the people inside them.

Instead of static awareness training, Adaptive delivers behavior-first simulations that reveal real risk, reinforce verification habits, and improve decision-making under pressure. With Adaptive, organizations can:

- Surface and reduce human risk before it leads to incidents by identifying vulnerable behaviors across roles and response patterns.

- Strengthen employee judgment against AI-driven impersonation attacks so deepfakes, voice clones, and fake executives don't trigger costly mistakes.

- Improve real-world response across critical teams with training that aligns to each role's access, authority, and attack exposure.

The goal isn't just awareness—it's readiness. See how Adaptive simulates threats others can't. Book a demo today.

FAQs about social engineering attacks

How common are social engineering attacks?

Extremely common and growing. IBM's 2024 X‑Force Threat Intelligence Index reported that phishing and other social engineering techniques were the leading cause of initial access in cyberattacks.

Nearly 70% of breaches still involve human factors like manipulation or error. These attacks are cost-effective for adversaries and hard to detect through traditional technical defenses alone.

How can you prevent social engineering attacks?

Preventing social engineering starts with layered defense: technical controls (like MFA and email filters), strict verification protocols, and, most importantly, empowering your people to spot and resist manipulation. Simulated attack training, culture change, and behavior-based policies are critical in reducing risk at scale.

How can training reduce the impact of social engineering attacks?

Effective security awareness training builds behavioral reflexes. Instead of one-size-fits-all modules, Adaptive Security uses targeted simulations and role-based scenarios to teach employees how to identify and interrupt social engineering tactics. Over time, this reduces successful attack rates, improves response times, and builds lasting security awareness.

Why do cyber attackers commonly use social engineering attacks?

Because they work. Technical systems are getting harder to breach, but people remain susceptible. Scammers exploit trust, urgency, fear, or helpfulness to bypass controls without triggering alarms.

Social engineering is also cheap, scalable, and adaptable, making it a go-to weapon in the modern cybercriminal's toolkit.

As experts in cybersecurity insights and AI threat analysis, the Adaptive Security Team is sharing its expertise with organizations.

Contents