Most cyberattacks don't start with broken code—they start with a yes. One hurried reply to a fake IT alert, one "urgent" request that looks like it came from a boss, or one QR code that leads to a convincing login page and the door is wide open.

These are all common social engineering scenarios. Social engineering works because it targets people, not firewalls. Attackers use pressure, authority, and believable stories to get employees to share passwords, bypass MFA, send money, or reveal sensitive data.

Verizon's 2025 Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR) found that the human element is involved in 60% of cybersecurity breaches (e.g., clicking a malicious link, being manipulated during a phone call, or sending data to the wrong recipient).

When social engineering succeeds, the damage can be costly. The FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) reports Business Email Compromise (BEC) losses of $2.77B in 2024.

This article breaks down six common examples of social engineering, so you know what they look like in the real world and what to do to stop them.

What is social engineering?

Social engineering is a tactic where attackers manipulate people into performing actions that help the attacker, such as sharing passwords, sending money, granting access, or revealing sensitive information.

Social engineering typically follows a familiar pattern. Attackers begin by sounding credible. They reference a real coworker or a situation that fits naturally into your day. They then create urgency, ask for a small action (click, scan, approve), and exploit normal human instincts to gain access to credit card details or funds.

Attackers rely on the same psychological levers every time, just delivered in different forms:

- Trust: Attackers impersonate a trusted sender (HR/IT/your bank/a vendor), so you assume it's legitimate and don't verify.

- Authority: They pose as someone higher up (CEO, legal, audit) so you feel you can't question them. For example, something like "CFO needs this wire approved in the next hour—don't delay."

- Urgency: They create a tight deadline so you act fast and skip checks. You'd receive a message like, "Payroll runs in 30 minutes—confirm your details now," which compels you to act quickly without first verifying.

- Curiosity: They bait you with something you'll want to see, so you click before thinking—something like, "Is this you in this photo/video?" or "Updated org chart. See the attachment."

- Habit: They copy routine work requests you do on autopilot, so it feels normal. Common examples include "DocuSign: review and sign," "Password reset required," and "Invoice approval needed."

The most common categories of social engineering

You'll hear a lot of "-ishing" terms, but most types of social engineering attacks fit into a few buckets:

- Phishing attacks: A mass scam message that tries to get you to click a link or enter your login details by pretending to be a real service (like IT, DocuSign, or a shared file).

- Spear phishing/whaling: A phishing message written for a specific person (or exec) using real details, so it feels legit and gets you to click, log in, or approve something.

- Pretexting: A fabricated scenario that sounds plausible ("I'm on a call with the CFO, need this now")

- Business Email Compromise (BEC): An impersonation scam aimed at money, where attackers often pose as a boss or vendor to get you to send a wire or change bank details.

- Smishing/vishing: Phishing done over text (smishing) or phone/voicemail (vishing), usually to steal logins, multi-factor authentication (MFA) codes, or payments.

- Quishing: phishing delivered via QR codes. Threat actors prompt you to scan it, then redirect you to a fake login or payment page that steals your credentials.

- Baiting: Lures that use temptation or curiosity (gift cards, "free" downloads, a "resume," or a USB) to get you to open something unsafe.

- Tailgating/piggybacking: A physical trick where someone gets into a secure area by walking in behind an employee who holds the door out of politeness.

In Verizon's dataset of social engineering incidents, pretexting accounts for over 40% of incidents, and phishing accounts for 31%. This is a good reminder that attackers don't need advanced techniques; they just need believable stories.

With those patterns in mind, here's how they show up in real attacks.

Example 1: CEO fraud and deepfake voicemails

CEO fraud isn't new. What's new is how convincing it's become.

For years, attackers have relied on spoofed emails pretending to be from a CEO, asking for an urgent wire transfer. Today, they're skipping the inbox and creating AI-generated voicemails that sound exactly like your executive leadership.

In 2024, Hong Kong police faced a similar case in which a finance employee transferred $25 million after joining a video call with senior executives, all of whom were AI-generated deepfakes. The voices, faces, and mannerisms were convincing enough to pass initial scrutiny. The company later confirmed it was a deepfake-enabled social engineering attack.

Why deepfake CEO fraud works

AI-enabled deepfake CEO fraud doesn't work because employees are careless. It works because it mirrors how real organizations operate under pressure. When a request appears to come from the CEO or CFO, authority kicks in.

Manipulative tactics like urgency ("this can't wait"), familiarity (a voice that sounds right), and secrecy ("don't loop anyone else in") push even well-trained employees to act fast instead of verifying.

AI voice cloning removes the last natural warning sign. With short audio samples from earnings calls, interviews, or internal meetings, attackers can convincingly replicate tone, pacing, and accent.

Deepfake voicemails also bypass traditional verification because many companies still rely on outdated assumptions about identity.

- Voice is no longer proof: Recognizing someone's voice is no longer sufficient for authentication.

- Voicemail avoids friction: There's no chance to ask follow-up questions or challenge the request in real time.

- Channel-stacking increases credibility: A voicemail followed by an email, Teams message, or document creates a false sense of confidence.

- Attackers target roles, not systems: They single out finance, HR, IT, and exec assistants because they can act quickly and often alone.

CEO fraud continues to succeed even in security-aware organizations because the attack isn't technical; it's procedural and human.

Example 2: Phishing via Google Sites link

Most people are taught to hover over links and look for sketchy domains. That advice falls apart when the link points to Google.

In this attack, scammers host phishing pages on Google Sites. Because it runs on a trusted Google.com subdomain, it bypasses many forms of cybersecurity resilience that organizations have built over the years.

When a link begins with sites.google.com, people often assume it's a legitimate Google page. They click quickly, only realizing something is wrong after being funneled into a fake login screen.

The strategy isn't novel. Like any good con, the attack relies on familiar psychological pressure points, simply wrapped in a more convincing disguise.

There are real-world examples of phishing scams that use Google Sites.

For example, in April 2025, software developer Nick Johnson (founder and lead developer of Ethereum Name Service) tweeted that he had been targeted by a sophisticated phishing attempt that leveraged Google's own infrastructure against him.

The email landed in his Gmail inbox, appearing to come from Google, passed authentication checks, and used a legal scare tactic ("a subpoena was served") to create panic and urgency. The hook was a "Google Support Case" link that appeared legitimate at a glance, but it pointed to a Google Sites page rather than an official Google support domain.

https://x.com/nicksdjohnson/status/1912439023982834120

Once you clicked through, the fake support page used pressure cues such as "IN PROGRESS" and "URGENT" labels, then funneled the victim to buttons like "View case" or "Upload additional documents," which redirected to a login page designed to look identical to Google's real sign-in page.

The goal was simple: steal credentials while everything still felt "inside Google."

Why this works (and why it's so hard to spot)

This attack succeeds because it borrows credibility from systems people trust and use every day:

- It's on a Google domain: A sites.google.com link doesn't trigger the same suspicion as a random domain.

- It looks like normal work: Support cases, document links, account alerts, and "verify your account" flows are everyday muscle memory.

- The email can pass checks and still be malicious: In Johnson's example, Gmail displayed it as coming from Google, but the message contained discrepancies (including "mailed by" details that didn't match Google).

- It uses fear and urgency to narrow your thinking: A "subpoena" notice is designed to make you react before you verify.

Example 3: SMS-based package delivery (smishing)

Package-delivery smishing works because it hits you at the exact moment you're most likely to click—when you're expecting parcels and juggling a dozen tracking updates.

The text typically states there's a delivery issue (e.g., your address is incomplete or your parcel is stuck at a depot) and then includes a link that appears to be a courier site.

In the U.S., the FTC reported that fake package-delivery scam texts were the most reported text scams in 2024, with consumers reporting $470 million in losses from scams that started with text messages.

The Guardian also described a "spray and pay" wave around Black Friday and Christmas, in which criminals send thousands of delivery texts and request a £1–£2 redelivery charge to "rebook" a parcel that doesn't exist.

Evri, a British courier company, told The Guardian it received 10,000 delivery-fraud reports between November 2024 and January 2025, stressing that it never charges redelivery fees. The same warnings note that some fake parcel texts also try to trick you into installing malware, turning a "missed delivery" into device compromise.

Why this works (how urgency and curiosity do the damage)

A text that says your parcel is stuck or will be returned creates urgency, and a vague message ("we couldn't deliver your parcel") triggers curiosity, especially if you've ordered something recently.

Attackers often keep the request tiny (like a £1–£2 fee) because it feels too small to be a scam, but the real objective is rarely the fee. It's to get you to do one of these things:

- Enter card details (so they can charge more later or sell the data)

- Share personal info (name, address, phone, or email for future scams)

- Log in (credential theft)

- Install something (malware or a "delivery app" that compromises your device)

Delivery smishing continues to work because it appears more as a minor inconvenience you can clear in 30 seconds rather than a scam.

Example 4: Pretexting for payroll access

Payroll pretexting is one of the most effective social engineering tactics because it appears to be routine administrative work. The attacker impersonates a real employee (or HR/payroll) and requests a simple change (like updating direct deposit details), so the next paycheck is deposited into an account they control.

In a 2024 case reported in Darien, Connecticut, police report that a scammer gained access to an employee's email and sent the company a message requesting a change to her direct-deposit details. Payroll made the change, and the employee's next eight paychecks (about $15,351) were sent to a bank account controlled by the attacker before anyone noticed.

Why pretexting works (authority bias and believable context)

Attackers win here because they make the request seem like a normal workplace routine, not suspicious drama:

- It appears to be a standard payroll request: "I need to update my bank details" is routine, so your brain classifies it as low risk.

- It uses authority and process pressure: If the message appears to be from an employee (or HR), the recipient is more likely to be helpful, especially as payroll deadlines approach.

- It's designed to avoid scrutiny: The ask is small, specific, and time-bound, which nudges you into "just get it done" mode instead of "verify first" mode.

- The damage is delayed: The victim often finds out on payday, when reversing the change is harder, and the funds may already be moved.

Example 5: Physical tailgating into offices

Tailgating turns a social habit into a security gap. In most offices, the front door is a choke point where people move quickly, carry items, and try not to be rude.

If someone looks like they belong, dressed in business casual with a laptop bag and calm confidence, your brain stops registering them as a stranger and starts treating them like part of the normal office flow. The key is that the attacker completely blends in.

A real-world example shows how quickly things can escalate once someone is inside. In August 2017, the U.S. Attorney's Office (District of Massachusetts) announced charges against Dong Liu after an alleged attempt to steal trade secrets and computer information from Medrobotics in Raynham, Massachusetts.

According to the complaint, the CEO observed Liu in the company's secure area late in the day with multiple laptops, and the visitor log showed he hadn't signed in, in violation of company policy. When police questioned him, Liu gave conflicting explanations about how he entered.

Whether the entry point was tailgating or a breakdown in visitor check-in, it's clear that once someone blends in past the front door, they can move close to people, rooms, screens, and sensitive work without "hacking" anything.

Why tailgating works

Tailgating succeeds because it exploits how workplaces actually run:

- Helpfulness bias: Holding the door feels polite, not risky.

- Belonging cues: "A badge with a laptop and a confident walk" reads as an employee, even when it isn't.

- No one wants conflict: Challenging a stranger can feel awkward, especially if they seem annoyed, rushed, or familiar.

- Diffusion of responsibility: People assume "someone else" verified them (reception, security, their manager).

Example 6: QR code "quishing" at events

QR codes are everywhere at conferences and public venues, including during check-in, schedules, menus, "scan to join the Wi-Fi," and "scan to download the slides."

That convenience is exactly the problem. Quishing works because scanning feels safer than clicking, and people treat a printed QR code as a neutral signpost rather than a potential trap.

This is already showing up in the events world. A November 2025 report on quishing in business events described an anti-fraud convention in Singapore where attendees were shown a fake QR code promising to help them "skip the queue," a simple demo that proved how quickly convenience overrides caution.

From there, the QR code sent attendees to a rogue microsite that mimicked the organizer's branding (fake sponsor/speaker listings, "download the agenda," "claim your badge," "fill feedback form") or deep-linked them into a "login" or "verification" flow.

Beyond data theft, such malicious QR links can also install malware, which is especially risky at B2B conferences where devices may contain client communications, internal documents, and sensitive contacts.

Why quishing works (especially at conferences and public events):

- Convenience overrides caution: "Scan to skip the line" is irresistible when you're juggling badges, bags, and schedules.

- You can't "hover" on a poster: QR codes hide the actual URL until you scan them, and many people don't review the link preview.

- Mobile slips past your usual defenses: Corporate email protections don't help much when the scan happens on a personal phone.

- Attackers exploit expected behavior: Event check-ins, payments, speaker decks, and Wi-Fi portals are common requests, so the request doesn't seem suspicious.

How Adaptive Security helps simulate and prevent social engineering threats

Most social engineering incidents don't happen because someone "didn't know better." They happen because the attack fits neatly into a normal work moment. It could be a rushed request from leadership, a routine-looking payroll update, or a Google link that looks safe.

That's why annual awareness training isn't enough. In the moment, people click because they're rushed and the request feels routine. The fix is repetition and realistic practice until "verify first" becomes muscle memory.

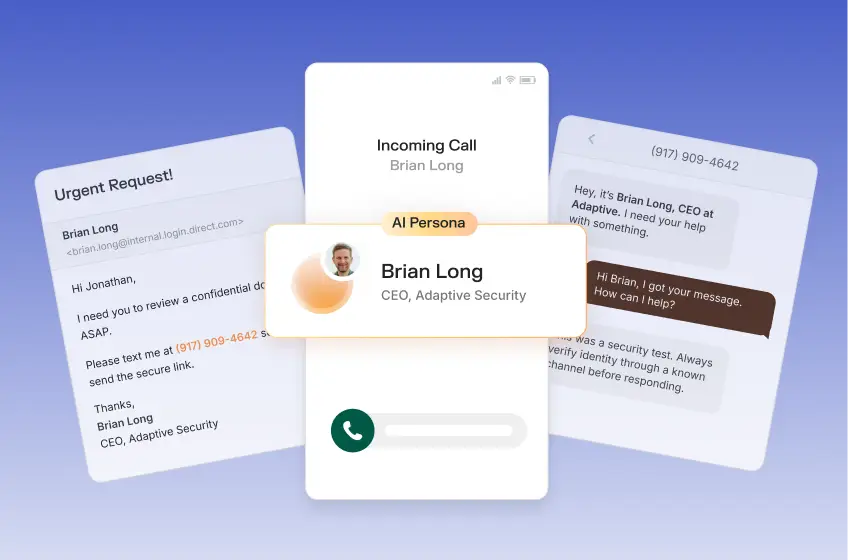

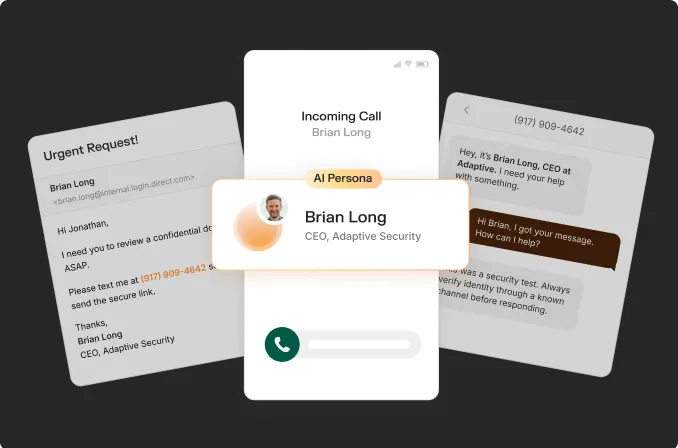

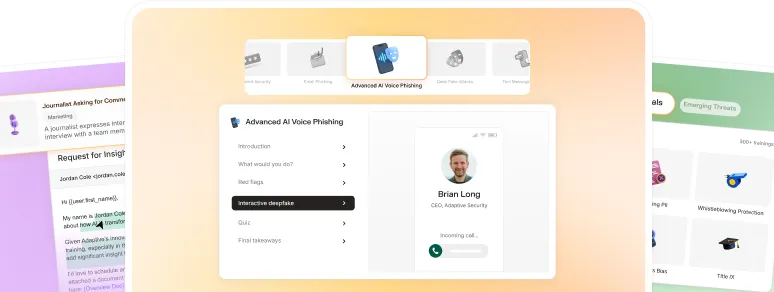

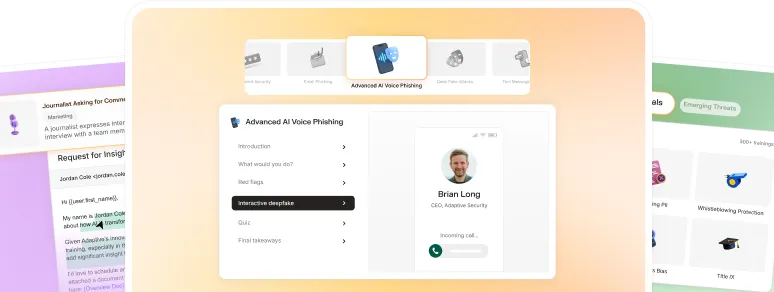

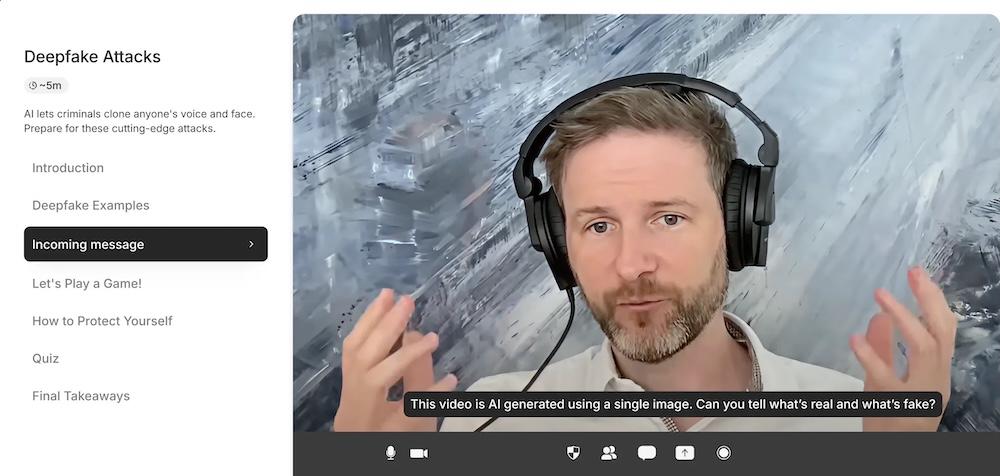

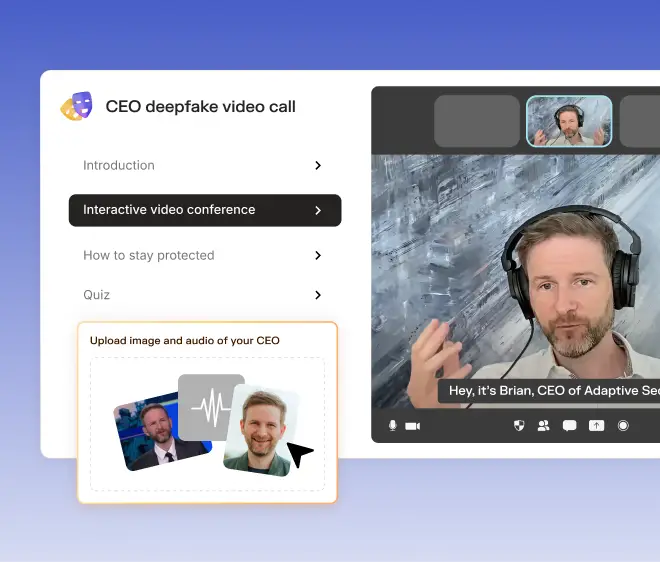

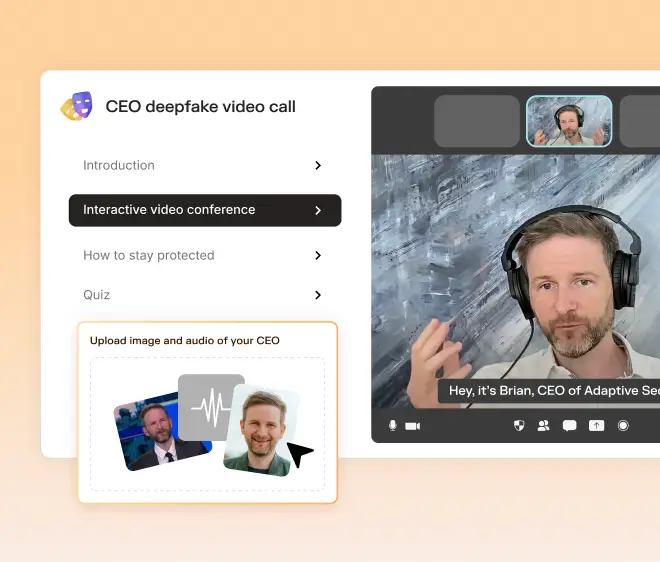

Adaptive Security, an AI-based security awareness training platform, addresses this by turning social engineering into practice. Instead of generic training, it lets you run realistic simulations across the channels people actually use (email, SMS, and even voice/video deepfake scenarios) so you can see how your team responds under real pressure.

Here's the range of scenarios attackers are actually using now that Adaptive can help you practice for:

- Deepfake impersonation and CEO fraud (voice/video deepfakes that feel "real")

- Phishing and credential traps (including "trusted-looking" lures and realistic landing pages)

- Smishing and mobile-first scams (delivery texts, "verify now," account alerts over SMS)

- Pretexting and role-based requests (payroll changes, HR requests, IT support "account recovery")

By running realistic simulations (such as a simulated payroll change request or a CEO's "urgent" message), Adaptive helps you identify which teams click, share information, or skip verification. You can then train on those exact scenarios until the safer response becomes the default.

Find out how your team would respond to these kinds of real-world attacks. Book a demo today.

FAQs about social engineering examples

What are the most common social engineering attacks?

The most common social engineering examples include phishing emails, fake delivery texts sent to your phone number, and a cybercriminal masquerading as IT, HR, or a vendor.

You'll also see quid pro quo scams ("do this and you'll get access/help"), and in-person tactics like tailgating into offices.

Attackers often use social media to gather details and make the story feel real. Each one is a form of social engineering designed to get you to click, pay, or share access.

How can I identify a social engineering attempt?

Start by treating any unexpected request as suspicious, even if it looks official. If someone asks you to log in, verify, or reset something, go directly to the service instead of clicking a link and checking your email account activity.

Be careful with messages that reference your role or profile from LinkedIn. Watch for impersonation of government agencies or internal teams, especially when they ask for confidential information. Turn on MFA, and never approve prompts you didn't initiate.

Why does social engineering work so well?

Because it relies on psychological manipulation rather than code. Attackers create urgency, authority, or fear to prompt you to act before you verify, and that pressure can lead to human error even in well-trained teams.

Social engineering also blends into routine work, using messages that appear to be routine requests rather than obvious cyber threats.

What should employees do if they suspect a social engineering attack?

Pause and don't engage. Report it using your internal process, then verify the request through a known channel. Don't share credentials, bank details, or your social security number.

If you clicked, disconnect and tell IT so they can check your endpoint for malicious software. Don't forget to keep your antivirus up to date to reduce risk.

As experts in cybersecurity insights and AI threat analysis, the Adaptive Security Team is sharing its expertise with organizations.

Contents